The practice of digital transformation: four non-tech skills for introducing change and innovation

Introducing change and innovation at large organisations can be a daunting task. Solutions that seem clear at a high level can get messy when you get into the details. There are lots of stakeholders, they all have their own take on the problem, and so you get varying degrees of support depending on what angle you take at any given moment. It can quickly spiral out of control into the feeling that “everything is related to everything,” making it hard to get going.

A common approach is to segment a part of the organisation and force change up on it. Another is to build an area of excellence off to the side — start from scratch, and then attempt to integrate the new effort into the organisation once it’s up and running. They can work, but success is often short-lived because, ultimately, you’re sidestepping the realities of organisational complexity. We’ve developed an approach that takes organisational complexity head-on without having to fight the battles associated with many transformation efforts.

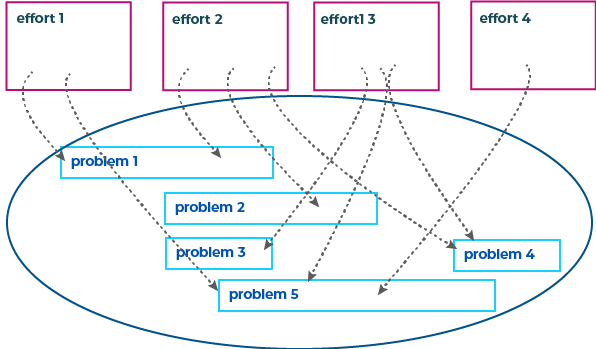

To do this, we start by mapping existing organisational activity and then establishing the new work within the mental model that’s already known to everyone. This mapping becomes a tool to minimise the novelty and associated mental load for others that can get in the way of innovation. You’ll need to look at these organisational factors:

- related efforts – what’s currently being done in the organisation that feels similar

- problem spaces – the other end of the issue, problems can have overlap with each other and with separate efforts

- history – how the organisation is built around having solved problems in the past

- language – how people talk about their efforts, the solutions they think they’re providing, their tools and methods hold a hidden power

Looking at these on an ongoing basis provides you with a living map to navigate the various layers of complexity, most of it non-technical, that can stop transformative change.

First, mapping related efforts

Change is rarely introduced in a vacuum. This creates immediate problems for innovation and change efforts. They can either be seen as too novel and therefore risky. Success in large organisations is rarely attached to risk. On the other hand, they can seem too similar to existing efforts, leading to questions of purpose and value.

To get past these issues, start by mapping related efforts so that you can become an expert at understanding, and then communicating, similarities and differences — highlighting the value of new efforts while keeping them grounded in the existing mental models that people already have. Map the shared attributes of these efforts:

- people (often work on more than one effort)

- shared resources (data, for instance)

- similar methodologies & tools used to achieve different ends

- similar-sounding language used for distinct purposes, especially across teams

- budgeting and organisation, common causes duplication of effort

We use the term related efforts to distinguish from competing efforts, which attempt to solve the same problem.

I recently worked on a programme to deal with fraud in digital services. In most people’s minds, that means doing identity assurance — making sure someone is who they say they are. Our programme, however, was dealing with what happens afterward, with the vast amount of data and money that flows out of services through otherwise legitimate interactions. These two areas have a lot of overlap, but are quite different when you get down into the details. Another distinction we had to clarify is that we weren’t dealing with the type of fraud that stems from internal problems such as corrupt contract awards.

So, two things we had to map and understand were the limits of identity assurance efforts, and also all the different types of fraud, who was the current owner in the organisation, and what was their take on digital fraud.

The next time we ran into someone at the very senior level, when we were able to clarify all the distinctions and positions for them right up-front, in one-or-two sentences. He could see why we were different, where we could add value, and how our work would benefit and dovetail with his. We weren’t a threat, so we had an immediate ally rather than a potential adversary.

Understand how problems are related to and viewed by the people working on them

A second layer of complexity is the problem space — a set of problems that a group identifies with. This gives us a clearer picture of why related efforts come about. Separate groups will create efforts to solve their version of the problem. That’s because organisational problems are often bigger than just one group. When you’re introducing change to deal with a problem, you are bound to have multiple views both the problem and its solutions, each tailored to the specific needs of one group. When a set of problems are given a short-hand and treated as one problem by a group, it’s difficult to talk about specific problems and specific solutions.

Telling themes we’ve encountered:

- “If we just had technology x, we could increase our ability to handle customer support, and reduce our customer support costs”

- “If we just replaced technology y with technology z, our data-related problems would be greatly reduced”

In both cases, the problem we were looking at was more complex than implied by the simplifications “high customer support costs” or “data problems”.

In the case of high customer support costs, we were dealing with three issues:

- one group had problems with their service

- another was an organisation-wide problem related to the new authentication system

- the third was that support agents, being squeezed for time had insufficient training

In none of the cases would the “technology x” have helped. But, because the group that had the budget and access to “technology x” worked with all these teams, it was being pushed as the solution.

The data issue followed a similar pattern — multiple groups had problems that were in some way data-related. Because “data” (which can mean anything these days) was the only thing they had in common, then it became the default to talk about the cross-organisational problems as if it was one single problem.

Getting to this level of understanding usually means spending time with the most front-line operational staff or customers, talking about problems as they experience them, and staying away from discussions about specific technology or proposed solutions.

When you can speak the language of problems, from the perspective of different stakeholders, you’ve got another tool that’s going to help you introduce change. Taking the time to gain perspectives buys trust and also prevents you from barreling forward with a solution that may not be needed.

Understand history – today’s problems are yesterday’s solutions

A really good way to kill support for your totally awesome innovation project is by running around pointing out the failures of others. This can happen unintentionally when you announce how fantastic the new thing you’re doing will be. Quite often, there is quite a bit of history around previous efforts, and very nice people put a lot of work into those efforts. The people involved may have been victims of compromise or other unknown factors. More likely, things that look problematic today were just a solution to a past problem.

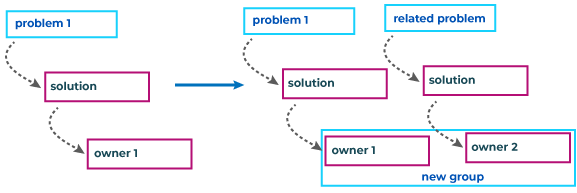

One way you’ll encounter this in very large organisations is their tendency toward creating teams around problem spaces. The progression goes something like: a solution is put in place for a problem or need, and that solution (usually tech) is given to an owner. After a while, a related problem is also given a related solution, and the team grows into a group.

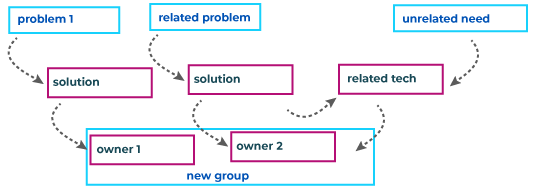

Then, as the organisation progresses and the problem changes, the original group gets re-purposed for the sometimes-related new problem or solution. Often, though, it’s hard to tell what the relationship is without the history:

Technology transformations will naturally clash with these specialised groups for a couple of reasons. The human aspect is often overlooked. Imagine that you’re the kind of person who comes into work every day and gets a bit of meaning out of life from solving problems for others, you’re the best, and it’s no one else’s thing. The idea that someone else, without your experience, with something new is going to do a better job than you can be both a little insulting and also quite frightening.

What it means for this type of worker is that either things must change (very few people like change), or they’re out of a job. The existential threat this creates in individuals often surfaces as the most difficult problem with transformation efforts: “digging in” — where no matter what you do new requirements and barriers are constantly created to stem the tide of change. At the bottom of this is that the group’s identity is grounded in the only thing that’s related — tech, rather than purpose.

The solution here is to map from the history to today, and then to a point in the future for those that are affected.

When a transformation effort is focused solely on technology delivery this can fall through the cracks. On the one hand, is it really a delivery team’s job to understand skills gaps and involve themselves in enterprise resource planning? On the other hand, it’s difficult to know what changes are going to be needed before an innovation is introduced, because the impact is so difficult to predict.

So, it’s enough to map the “as-is” at the beginning of an effort, but it’s also important to have ongoing conversations with group leaders affected by change so that realistic information is reaching them at the soonest possible moment.

Language and the power of naming

This one’s last, not because it’s the least important, but because it sits under everything else.

As you explore related efforts, problem spaces, and history, you’ll notice that the names of those efforts, problems, and the groups charged with addressing them tend to change throughout time. Rather than dismissing this as an annoyance or an artifact of bureaucracy, you should learn to take note. The relationships between named things and the speakers can be a treasure trove of information that will later determine your ability to succeed.

Some will still use the name of the organization or group from last decade, conferring their age, knowledge, and informal status. Others will use acronyms without digging further into the meaning, marking you as an outsider. From here we have only a broad general term for something that’s considered three things over there. And so on.

So, names provide a view into the organisation’s history, relationships, alliances and grudges. All valuable information when introducing change. But the last thing that language exposes is frontiers. And this is where you come in.

If you’re actually innovating and changing not just an organisation, but an industry, then chances are that names for what you’re doing aren’t quite there yet. When you reach this boundary, it’s usually a good prompt to look across industries, maybe into academia. More helpfully, the world of marketing and communications has plenty of tools that you can borrow in order to provide language for something new that’s grounded in something familiar from the past (a topic for another day).

Building your discipline

Together, these begin to form a practice of transformation. It’s important to think about transformation as a practice, rather than an outcome — we now live in a world of constant change. In order to manage the huge volume of information that a transformation leader deals with, that practice must provide a disciplined manner of capturing, organising, and then referencing many related concepts.

The ability to quickly draw on any particular facet of a very complicated organisational change story becomes possible when you can navigate related efforts and problem spaces. Being able to communicate that perspective to the present stakeholder through a shared language and common view of history provides you with the most important aspect of organisational change: managing and maintaining relationships.

We’re constantly working on our methodologies, so we encourage you to start thinking about your past success and what about it is repeatable. Transformation is no longer about just introducing technology and agile methodologies, it’s the discipline of managing constant change, and one that we’re all learning together — that’s exciting.